The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City holds over thirty thousand works of art from Greek and Roman cultures

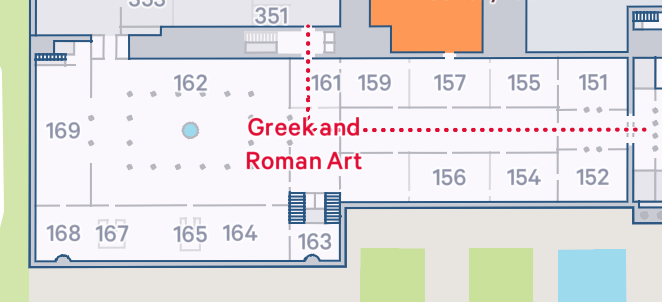

The Greek and Roman department at the MET houses a diverse range of artworks, including sculptures, pottery, jewelry, coins, and other artifacts. These items span from various periods, styles, and regions within the ancient world of Greece, as well as overlapping into the Ancient Roman era. The collection in NYC is the second largest of Attic sculpture in the world, next to Athens itself.

The first additions to the museum were from a Roman sarcophagus in 1870, where a few years later, founding director Luigi Palma di Cesnola began showing the artworks. By 1910, Edward Robinson (third director) continued adding to the department with his findings sourced from bequest, gift, and purchase.

People such as J. P. Morgan and Jacob S. Rogers assisted in the acquisition of Greek and Roman art through donation at a large scale.

A specific department to house the large number of works was not officially established until 1909 with its former title, the Department of Classical Art. In 1935, the title was changed to the Department of Greek and Roman Art to better suit the collection.

While the Metropolitan Museum of Art is no doubt a breathe-taking attraction, its necessary to acknowledge if interpreting art outside of it's home origin takes away from the experience, if its morally acceptable to take art out of its home, how the MET follows repatriation procedure, and the legal process of acquiring art.

The first additions to the museum were from a Roman sarcophagus in 1870, where a few years later, founding director Luigi Palma di Cesnola began showing the artworks. By 1910, Edward Robinson (third director) continued adding to the department with his findings sourced from bequest, gift, and purchase.

People such as J. P. Morgan and Jacob S. Rogers assisted in the acquisition of Greek and Roman art through donation at a large scale.

A specific department to house the large number of works was not officially established until 1909 with its former title, the Department of Classical Art. In 1935, the title was changed to the Department of Greek and Roman Art to better suit the collection.

While the Metropolitan Museum of Art is no doubt a breathe-taking attraction, its necessary to acknowledge if interpreting art outside of it's home origin takes away from the experience, if its morally acceptable to take art out of its home, how the MET follows repatriation procedure, and the legal process of acquiring art.

Does the Metropolitan Museum of Art successfully represent Greek art?

Art played a critical role in the political and civic life of Ancient Greece. Buildings and sculptures were often commissioned by city-states to commemorate victories, honor leaders, and create pride. Public art became a means of expressing power and identity. So does removing these cultural items play a factor into the interpretation and understanding of them by their viewers in NYC?

In terms of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Greek art is displayed in an overwhelming amount. In the Greek and Roman department, over ten rooms are carefully curated with multiple examples of each and every category of Greek artifact imaginable. When looking at the collection as a whole, the viewer is fully immersed in the art of Greece. The MET allows its visitors to be closed off from the idea of 'New York' for a moment, and pushes its guests to enjoy a moment in Ancient Greece. In comparison, I like to think of the Metropolitan Museum with the analogy of family makes a house a home. The artifacts may be removed from their "house," but they are surrounded by artifacts alike them, allowing themselves to be at home.

In terms of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Greek art is displayed in an overwhelming amount. In the Greek and Roman department, over ten rooms are carefully curated with multiple examples of each and every category of Greek artifact imaginable. When looking at the collection as a whole, the viewer is fully immersed in the art of Greece. The MET allows its visitors to be closed off from the idea of 'New York' for a moment, and pushes its guests to enjoy a moment in Ancient Greece. In comparison, I like to think of the Metropolitan Museum with the analogy of family makes a house a home. The artifacts may be removed from their "house," but they are surrounded by artifacts alike them, allowing themselves to be at home.

Is it Morally acceptable to take art out of its origin?

The question of art belonging in its home country or if it's acceptable to display in other locations holds a lot of weight. It's important to acknowledge how exactly an item was acquired when determining if a third party can rightfully claim ownership of something they did not create. To better understand the moral dilemma of museums it's crucial to be aware of examples of art looting and cases of repatriation.

The NY-based Indian American art dealer, Subhash Kapoor, was found to have illegally acquired and sold around a hundred million dollars worth of stolen art in 2011. Over ten years later, repatriation cases are still ongoing across the States to bring home these works of art. Some examples of museums found to have done business with Kapoor are the Yale University Art Gallery, the Honolulu Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Asian Museum of Art in San Francisco, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Subhash Kapoor was caught when a shipment of artifacts being brought from India to New York were discovered to be stolen, followed by testimonies from involved individuals led Homeland Security to Kapoor. While Kapoor was convicted for art looting in India and now faces a prison sentence, stolen art is still being discovered in museums across the US in need of finding its way back home.

According to ArtNet, the MET gave a statement regarding the repatriation, "The Museum is committed to the responsible acquisition of archaeological art, and applies rigorous provenance standards both to new acquisitions and to works long in its collection. The Museum is actively reviewing the history of antiquities from suspect dealers. The Museum values highly its long-standing relationships with the government of India, and is pleased to resolve this matter."

But the problem doesn't stop there. Subhash Kapoor is one singular person found to have involvement in stolen artifacts, and this only involved India's history being brought to the US. Museums should not be accepting artifacts with the promise of where it was "said to be found,"documentation needs to be clear and accurate. The entire globe is filled with ongoing investigations of theft with countless museums being forced to repatriate items they consider to belong to them.

The NY-based Indian American art dealer, Subhash Kapoor, was found to have illegally acquired and sold around a hundred million dollars worth of stolen art in 2011. Over ten years later, repatriation cases are still ongoing across the States to bring home these works of art. Some examples of museums found to have done business with Kapoor are the Yale University Art Gallery, the Honolulu Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Asian Museum of Art in San Francisco, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Subhash Kapoor was caught when a shipment of artifacts being brought from India to New York were discovered to be stolen, followed by testimonies from involved individuals led Homeland Security to Kapoor. While Kapoor was convicted for art looting in India and now faces a prison sentence, stolen art is still being discovered in museums across the US in need of finding its way back home.

According to ArtNet, the MET gave a statement regarding the repatriation, "The Museum is committed to the responsible acquisition of archaeological art, and applies rigorous provenance standards both to new acquisitions and to works long in its collection. The Museum is actively reviewing the history of antiquities from suspect dealers. The Museum values highly its long-standing relationships with the government of India, and is pleased to resolve this matter."

But the problem doesn't stop there. Subhash Kapoor is one singular person found to have involvement in stolen artifacts, and this only involved India's history being brought to the US. Museums should not be accepting artifacts with the promise of where it was "said to be found,"documentation needs to be clear and accurate. The entire globe is filled with ongoing investigations of theft with countless museums being forced to repatriate items they consider to belong to them.

What if it was acquired legally?

While it's almost impossible for an art lover to sit back and enjoy a gallery while simultaneously knowing there are cultures upset over art stolen from them, it is exciting to have the opportunity to view art when traveling across the globe isn't an option. Personally, I have no desire to travel and never have, but growing up with access to museums such as the MET allowed me to fall in love with art. From the first time I walked into the MET I knew I had an interest in art. I was able to explore culture upon culture and understand the development of art through time, everything connecting and overlapping in a beautiful way. I do not think all art should stay in it's home country, I believe art is meant to be seen and should be held in locations where everyone has access. But this will never work if there are not rules, if there is not an understanding of what is right and what is wrong.

According to the MET's Collections Management Policy, in terms of purchase, "the curator recommending the work of art to be purchased writes a detailed report, including a description of the work, its condition, publication history, importance to the Museum’s collection, justification for acceptance, provenance, intentions for display (and/or storage) and publication and the gift or fund against which the purchase will be charged. A conservator and, when appropriate, a scientist must examine all proposed purchases and provide an analysis of the work and assessment of its condition, dating, and attribution as part of the report."

It's also important to note the statement, "The Museum is committed to the principle that all collecting be done according to the highest standards of ethical and professional practice." The MET hold itself to a certain standard when it comes to acquiring items through purchase and donation, but I keep finding myself with the question of if certain artworks are "said to be from..." or if there is actual documentation not accessible to the public. Even so, with specific information about the unearthing of items and direct purchases, laws protect those who acquired items before certain dates. Factors such as public access, educational value, and preservation sway me to want to keep art at Museums such as the MET, yet I can't forget about morals, ethics, restitution or repatriation, and the preservation of cultural heritage.

According to the MET's Collections Management Policy, in terms of purchase, "the curator recommending the work of art to be purchased writes a detailed report, including a description of the work, its condition, publication history, importance to the Museum’s collection, justification for acceptance, provenance, intentions for display (and/or storage) and publication and the gift or fund against which the purchase will be charged. A conservator and, when appropriate, a scientist must examine all proposed purchases and provide an analysis of the work and assessment of its condition, dating, and attribution as part of the report."

It's also important to note the statement, "The Museum is committed to the principle that all collecting be done according to the highest standards of ethical and professional practice." The MET hold itself to a certain standard when it comes to acquiring items through purchase and donation, but I keep finding myself with the question of if certain artworks are "said to be from..." or if there is actual documentation not accessible to the public. Even so, with specific information about the unearthing of items and direct purchases, laws protect those who acquired items before certain dates. Factors such as public access, educational value, and preservation sway me to want to keep art at Museums such as the MET, yet I can't forget about morals, ethics, restitution or repatriation, and the preservation of cultural heritage.

So...Would art be better interpreted in its home origin?

Overall, in terms of an art lover and historian, viewing artworks outside of their homes will change the way we interpret them. It adds an additional narrative to the piece that takes away from its intended purpose. Viewing Greek art within Greece will connect its an art lover to the lifestyle of Ancient Greece and the creators of the art without distracting them with curiosity of repatriation and the ongoing issues of looting. But, the general public won't bat an eye, they'll view these works for what they are without changing their interpretation. Especially in a location such as the MET, which allows its viewers to be immersed in the culture due to the size and organization of their collection. The Metropolitan Museum of Art makes its collection look like it belongs there, surrounded by artifacts that pair together beautifully, but its necessary that they all got there morally.

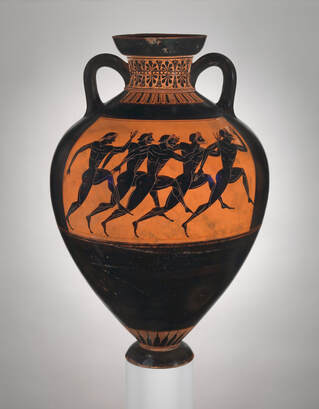

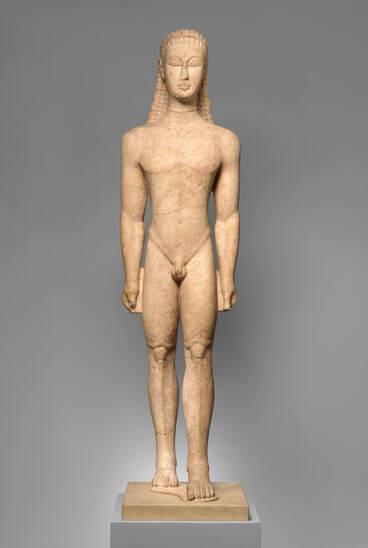

Lets take a closer look at some artworks on view at the MET:

References

“Bronze Diskos Thrower” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/247967#:~:text=This%20superlative%20bronze%20embodies%20the. Accessed 8 Dec. 2023.

Cascone, Sarah. “The Met Museum Returns More Looted Art to Greece and Turkey, Including 15 Antiquities Seized from Disgraced Dealer Subhash Kapoor.” Artnet News, 3 Apr. 2023, news.artnet.com/news/the-met-returns-more-looted-art-to-greece-and-turkey-2278882. Accessed 11 Dec. 2023.

“Greek and Roman Art.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/about-the-met/collection-areas/greek-and-roman-art. Accessed 22 Aug. 2023.

Kinsella, Eileen, and Judith Harris. “The Talks Begin.” ARTnews, vol. 105, no. 5, May 2006, p.59. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=21592232&site=eho st-live.

“Marble Grave Stele of a Little Girl.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2019, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/252890. Accessed 8 Dec. 2023.

Powell, Eric A. “The Met’s New Temple.” Archaeology, vol. 60, no. 4, July 2007, p. 16.EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=25281478&site=eho st-live.

“Subhash Kapoor: A Decade in Review.” Center for Art Law, 13 July 2021, itsartlaw.org/2021/07/13/subhash-kapoor-a-decade-in-review/.

“Terracotta Krater.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2019, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/248904. Accessed 8 Dec. 2023.

“Terracotta Panathenaic Prize Amphora.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2019, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/248902. Accessed 8 Dec. 2023.

Metropolitan Museum of Art Board of Trustees. “Collections Management Policy.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 3 Oct. 2023, https://www.metmuseum.org/-/media/files/about-the-met/policies-and-documents/collections-management-policy/Collection-Management-policy-10_5_23.pdf. Accessed 8 Dec, 2023.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Marble Statue of a Kouros (Youth).” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2019, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/253370. Accessed 8 Dec. 2023.

“Bronze Diskos Thrower” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/247967#:~:text=This%20superlative%20bronze%20embodies%20the. Accessed 8 Dec. 2023.

Cascone, Sarah. “The Met Museum Returns More Looted Art to Greece and Turkey, Including 15 Antiquities Seized from Disgraced Dealer Subhash Kapoor.” Artnet News, 3 Apr. 2023, news.artnet.com/news/the-met-returns-more-looted-art-to-greece-and-turkey-2278882. Accessed 11 Dec. 2023.

“Greek and Roman Art.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/about-the-met/collection-areas/greek-and-roman-art. Accessed 22 Aug. 2023.

Kinsella, Eileen, and Judith Harris. “The Talks Begin.” ARTnews, vol. 105, no. 5, May 2006, p.59. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=21592232&site=eho st-live.

“Marble Grave Stele of a Little Girl.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2019, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/252890. Accessed 8 Dec. 2023.

Powell, Eric A. “The Met’s New Temple.” Archaeology, vol. 60, no. 4, July 2007, p. 16.EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=25281478&site=eho st-live.

“Subhash Kapoor: A Decade in Review.” Center for Art Law, 13 July 2021, itsartlaw.org/2021/07/13/subhash-kapoor-a-decade-in-review/.

“Terracotta Krater.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2019, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/248904. Accessed 8 Dec. 2023.

“Terracotta Panathenaic Prize Amphora.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2019, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/248902. Accessed 8 Dec. 2023.

Metropolitan Museum of Art Board of Trustees. “Collections Management Policy.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 3 Oct. 2023, https://www.metmuseum.org/-/media/files/about-the-met/policies-and-documents/collections-management-policy/Collection-Management-policy-10_5_23.pdf. Accessed 8 Dec, 2023.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Marble Statue of a Kouros (Youth).” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2019, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/253370. Accessed 8 Dec. 2023.